When it pays to wear belt *and* suspenders

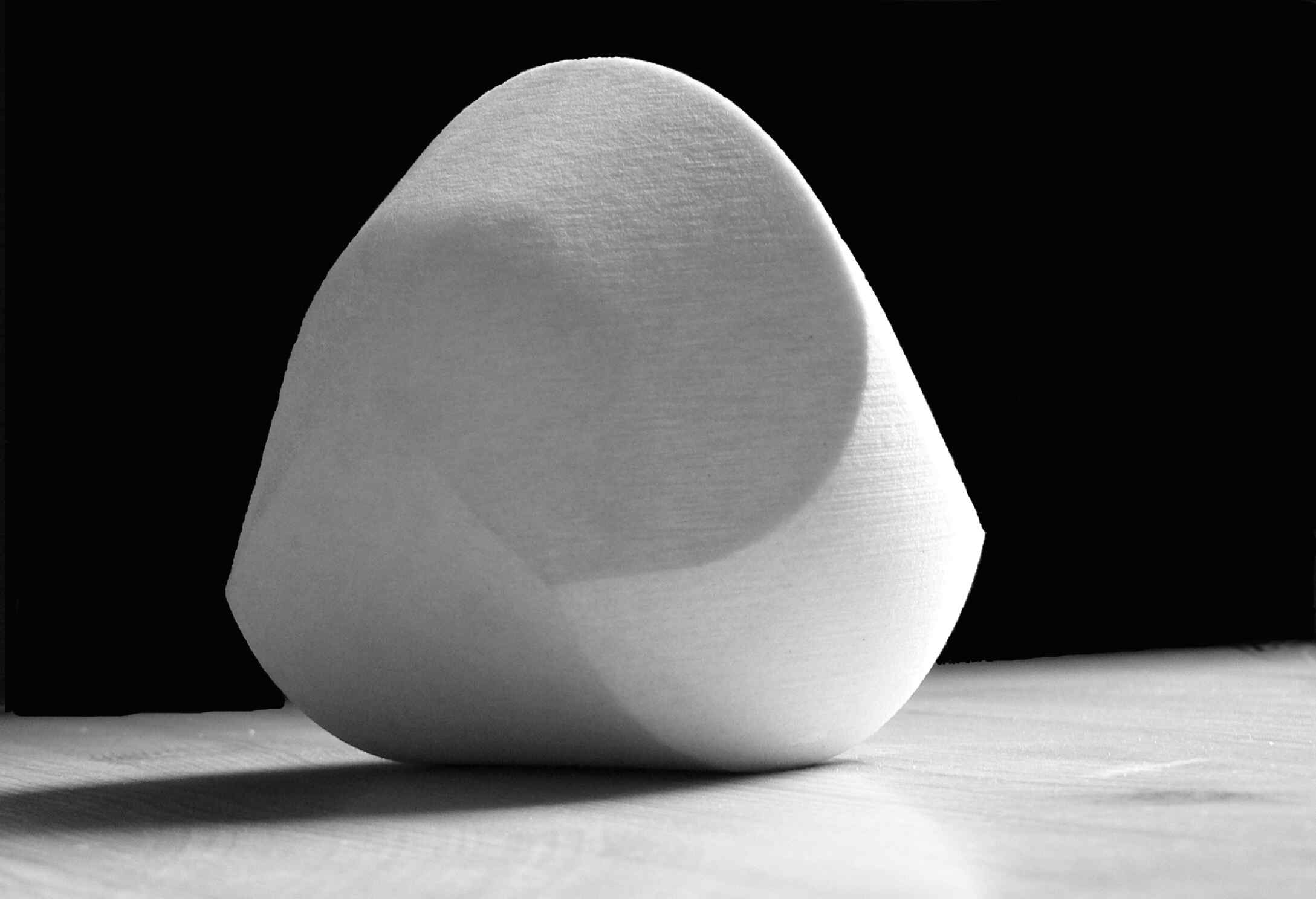

Hungary has given birth to several great inventors. Ernő Rubik invented — and patented — his Magic Cube in 1975. In 2006, Gábor Domokos and Péter Várkonyi came up with a weird object which had one stable and one unstable point of equilibrium and called it a “Gömböc”.

Photo: public domain

Hungarian IP lawyers have also been inventive. After Rubik’s patent expired, they actually managed to re-protect the cube as a three-dimensional EU trademark in 1999. The mark was contested in 2006 on the grounds that the shape was essential to the cube’s function; after 13 years of legal battles the CJEU decided in October 2019 (case T‑601/17) that if the shape of a thing is essential to its function, it cannot be protected as a 3D trademark.

In 2015, an application to protect the shape of Gömböc as a 3D trademark was filed in the Hungarian IP office, who refused. The decision was contested and ended up in the CJEU, who decided in April 2020 (case C‑237/19) that the assessment of whether a shape is essential to function does not have to be limited to the graphic representation of that shape.

The moral of this story?

If you really want to protect the results of your creative work, it might make sense to use multiple different IP instruments — patents, trade marks, and industrial designs, as well as copyright. Even if you manage to protect your invention as a piece of intellectual property, some kinds of IP will eventually expire and someone with strong enough motivation might be able to invalidate your rights in the meantime.

Originally posted on LinkedIn